Land connection practice + resource share

Re-connecting with life for ourselves & our world

Our land-connection practice group begins this coming Sunday (Oct 19), and if you’re interested I hope you’ll join us!

I also wanted to share some resources related to this curriculum that you might enjoy and benefit from, regardless whether or not you join us.

In the course Llywelyn will be providing concrete ideas and examples of what you can observe and document within your immediate environment - while contextualizing this within the larger biosphere, ecosphere & ecosystem within which you live AND grounding these experiences in a decolonial world view.

One helpful, big picture resource for locating your biosphere & ecosphere within the dynamic, living processes that we call “nature” is the One Earth Navigator tool. Check it out! You can narrow down biosphere (really big picture) to particular ecospheres … which gives you terminology and tools to further refine your understanding of the natural features and more-than-human beings (animal, plant, fungi, soil …) with whom you share your daily life.

Alongside the Western scientific tools for understanding ecological regions and ecosystems, we are encouraging all participants to use the Native Land Digital tool to gain insight into the Indigenous or First People’s of the land within which you reside. This is, of course, especially important and helpful for people who are settlers (like myself, in the United States).

So … what are next steps after you’ve identified the living community of beings within which you live (biosphere/ecosphere/ecosystem) AND the original people’s of this “land”?

I’ll use myself as an example. I live in Riverdale Park, MD - just outside of Washington, DC. Using the Native Land Digital tool affirms my knowledge that I live within Piscataway terriroty, as well as (more specifically) Nacotchtank (Anacostan). I live very close to the NE branch of the Anacostia River … the mere name of which grounds my daily life, and daily walks, within a recognition of the original people of this place.

Knowing the names of the Indigenous peoples of the territory in which I live gives me the tools to learn more of their story (past and present); their names and ways of utilizing, caring for and/or relating with the more then human world in this place; and a starting place for building relationship with and/or supporting the contemporary expressions of their struggle for survival and self determination.

Utilizing the One Earth Navigator, I can locate the larger natural systems within which I live from a Western scientific basis, which (again) provides me with tools and terminology to go deeper and find other resources to learn about and build relationship with the landscape and natural systems within which I live my life.

Another approach to understanding the web of life within which you are embedded is to identify what watershed you are living in (and, yes, We All Live in a Watershed!) I live in the Coastal Plain region of the Chesapeake Bay watershed - and have recently learned that I can look up native plants for my specific region using this tool. Perhaps there are similar online tools for your location.

Connecting with Indigenous and Western knowledge systems, as well as stepping into direct, solidarity-based relationships with the original inhabitants of the land within which we reside, is something Llywelyn and I hope will become an integrated part of land-connection for each of you over time. :)

To connect some of these “big picture” tools to a more granular, immediate observational practice that is similar to what Llywelyn will be sharing in the course, check out this lovely article by Vanessa Chakour: How to Reconnect With Nature Through Writing.

Here is a short sampling how Chakour frames this practice:

The wild is calling, and writing offers a powerful tool for reconnection. By taking the time to observe and reflect on our outdoor experiences, we begin to notice intricate details we might have otherwise missed: the delicate veins of a violet flower, the cool embrace beneath a linden tree in summer, or the haunting melody of a wood thrush. … The practice of nature writing can awaken our sense of wonder and a new appreciation for the living world around us.

The first step is slowing down, and the good news is, you don’t need to escape to a bucolic, remote landscape. Nature is everywhere, even in the heart of a bustling city.

Chakour then goes on to defining a few parameters for using writing to strengthen a connection to the natural world.

While Chakour does not contextualize her writing practice in an explicitly decolonial way, Llywelyn and I both strongly feel that building a strong connection to the more-than-human world within our daily lives is an essential component of building an equitable and sustainable society. While we will have to confront and replace the power structure of our current society in order for true renewal and connection to flourish - we also need to work on the “being” aspect of change if we want to build something that does not simply replicate the current systems of domination.

In this context, land connection practice is a very practical, grounded way to accompany and support our Indigenous siblings in the struggle to preserve and maintain functioning environmental systems and biological diversity in the face of capitalist/colonial destruction.

Here are some relevant reflections from the recent Native Perspectives on Public Lands teach-in, in which Lakota, Diné and Cherokee panelists speak about public lands and tribal preservation:

The idea of “owning” land is a foreign concept for Native peoples. The land is sentient. It encompasses many life forms and spaces. It holds immense energy.

From a Native perspective one cannot “own” land, yet one may live with the land.

Our regenerative relationships to land are based on generations of deep interconnectedness that have been taught through our cosmologies, ceremonies, and languages. Native peoples acknowledge that these on-going connections require responsibilities to the natural world. We provide offerings and prayers to the land for its healing.

Traditional teachings instruct us to maintain deep respect for land, life, and our four-legged and winged relatives — all our relations.

from Native Perspectives: Land Ownership

This same sentiment was expressed in a famous statement by Philip Blake, a Dene from Fort McPherson, as part of the 1975 Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry established by the Canadian government to investigate the environmental and social impacts of a proposed natural gas pipeline project. Here are some of Blake’s words:

If our Indian nation is being destroyed so that poor people of the world might get a chance to share this worlds riches, then as Indian people, I am sure that we would seriously consider giving up our resources. But do you really expect us to give up our life and our lands so that those few people who are the richest and most powerful in the world today can maintain their own position of privilege?

That is not our way.

I strongly believe that we do have something to offer your nation, however, something other than our minerals. I believe it is in the self interest of your own nation to allow the Indian nation to survive and develop in our own way, on our own land. For thousands of years we have lived with the land, we have taken care of the land, and the land has taken care of us. We did not believe that our society has to grow and expand and conquer new areas in order to fulfill our destiny as Indian people. ...

I believe your nation might wish to see us not as a relic from the past, but as a way of life, a system of values by which you may survive in the future. This we are willing to share.”

from Place against Empire: Understanding Indigenous AntiColonialism (Glen Coulthard)

The land-connection practice presented within the Building Relations with Land & Sky course is humble and immediate: taking the time to observe and record what is going on around you within the land, water and sky. It is a simple, non-appropriative practice that can be especially helpful for settlers (or anyone who does not have a strong connection to traditional, land-connection practices) to simply build our awareness and relationship with the natural world around us in a tangible, immediate way.

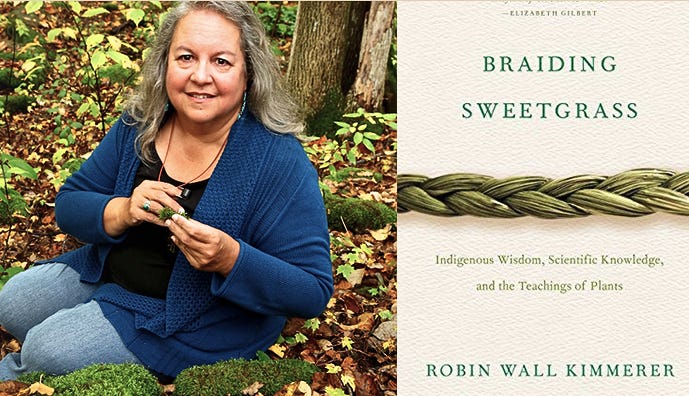

Neither Llywelyn nor I claim to be offering anything from, by or “on behalf of” our Indigenous comrades. We are, however, inspired and informed by their examples and their words as we remember that everyone on earth comes from people who (at some point in time) were deeply connected to land; that “land” is as set of living beings and relationships; and that building a sustainable and equitable human society requires living in grounded, practical and reciprocal relationship with the rest of life. As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes: “All thriving is mutual!”

Other supplemental resources we’ll be looking at during the course include Braiding Sweetgrass (by Kimmerer) and Sand Talk (by Tyson Yunkaporta). You may enjoy adding these books to your list of resources to support land-connection in your own life as well. And if you feel so inspired, I hope you will join us this Sunday, Oct 19, as we kick of the nature-connection course Building Relations with Land & Sky!

In solidarity,

Eleanor

PS: Last but not least, I want to give a special shout out to Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen and his project, Nordic Animism. Rune has been a profound resource for our annual ancestral recovery course, Before We Were White, for many years. If you aren’t already following Rune, you should check him out!